|

Narborough Bone

Mill

River Nar |

|

|

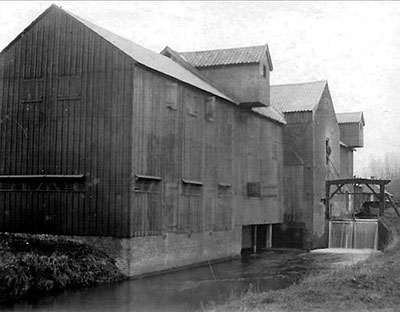

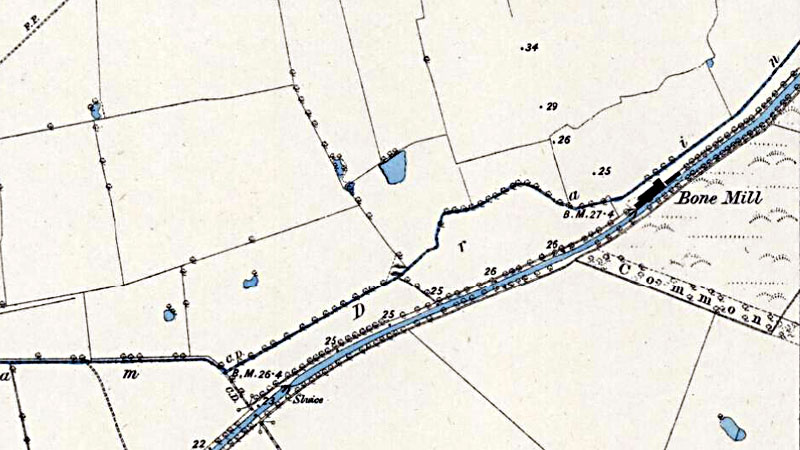

c.1880

|

|

Narborough Bone Mill was built in the early 19th century about 1½ miles downstream from Narborough Corn Mill. The fact that it was not near a road did not matter as both its raw materials and its finished products were carried by horse drawn barge. The mill converted bones from local slaughterhouses, Kings Lynn's whaling industry and Hamburg's cemeteries into agricultural fertilizer. The smell of the production process must have been distinctive and may well be part of the reason for the mill's chosen remote location. The mill probably

ceased production a few years after the Nar Valley Drainage Board purchased

the navigation rights and subsequently built a sluice that prevented further

river traffic around 1884. |

Please note: |

|

|

c.1880 |

|

Annie Coulton and brother Bill Denny in front of mill 1920 |

|

King’s Lynn relied heavily for a time on the whaling trade, a trade which brought a great deal of prosperity to the town, but which was also very risky. In 1775 the old Blubber house was built at Blubberhouse Creek. Horses towed the ships up the Nar to the site where the houses were. |

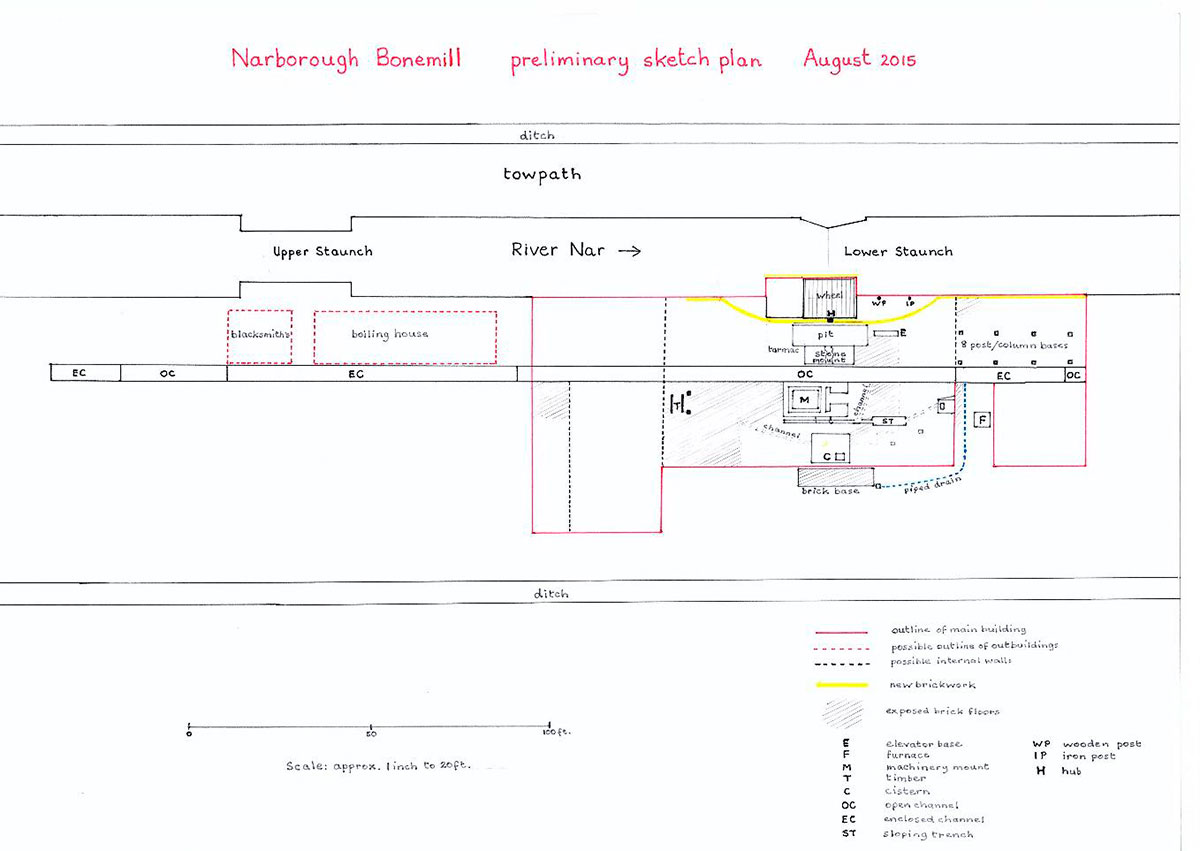

In 1751 plans were made to make the river Nar navigable from King's Lynn to Westacre. The requisite Act was passed before Parliament the same year, but it was not until 1759 that the first horse-drawn barges struggled up the river with their cargoes of coal and grain, and then only as far as Narborough. Water trade increased steadily over the years and received a boost when the Bone Mill was built, about a mile and a half downstream from Narborough. The mill, which is thought to date from the early nineteenth century, was owned from about 1830 by the Marriott brothers, who also built the Narborough Maltings and held the navigation rights. At the time of writing there is not much left to see, but the splendid cast-iron waterwheel, which generated the power for a thriving business in agricultural fertiliser, has so far resisted all attempts to shift it. Roughly crushed bones were used to renovate pastures in Britain in the late eighteenth century, but their action on the land was slow. By 1820 almost every major East Coast port had access to one or more crushing mills. White's Norfolk Directory for 1836 indicates that John Marsters and Company worked a bone mill at the Boal Wharf in King's Lynn, and with the Narborough Mill, produced the finely ground bone meal which proved to be more beneficial for East Anglian soils. In the early days of the Narborough Bone Mill a steady supply of whalebone came up river by barge from the blubber processing factory at Lynn. The sacks of bone meal were shipped back to Lynn, Cambridge and further afield. No whaling ships left Lynn after 1821, so the mill had to rely partly on collections made by 'bone wagon' from local farms and slaughterhouses. Villagers would sometimes take down "a penn'orth of bones to be ground" and supplies also came from North Germany. Shiploads arriving at Lynn would sometimes include the exhumations of burial grounds, but it is unlikely that anyone questioned the ethics of this, for it was said at the time that "one ton of German bone-dust saves the importation of ten tons of German corn". Details of the reduction process used at the mill are not known, but it is likely that the bones were first boiled to make them brittle and to remove the fat (skimmed off, perhaps, for use as coach and cart grease), then either chopped up by axes or put through toothed cylinders which gradually reduced the bones to small pieces. Finally, the millstones ground them into powder. After the Lynn and Dereham railway opened in 1846-7, the bone meal was transported up river to the Narborough Maltings, where the barges unloaded at the staithe. Most of the sacks of meal were then taken by horse-drawn wagons along the quarter mile of track to Narborough and Pentney station. From there it went to King's Lynn by train, but some was sold at the Maltings to local farmers, probably at the 'bone shed' marked on an old plan of the buildings there. The Bone Mill was built in a very isolated position, but the site must have been carefully chosen to obtain maximum efficiency for the working of the low-breast wheel. A stanch gate had been in existence since the river was made navigable, but this was probably replaced when the mill was built. At the same time, sixty yards upstream, a pair of mitre gates was added in the interests of the mill, creating a kind of pound lock between the two stanches. The mill race was taken directly from this partly walled chamber. The addition of the mitre gates was necessary in order to prevent the whole 1,100 yard stretch of river up the next stanch (Narborough Lower Stanch) being emptied each time a barge passed through the Bone Mill stanches. If this had happened, the wheel would have been put out of action until the water level built up again. The Nar navigation enterprise was abandoned in 1884 and the Bone Mill must have ceased production soon after. It is possible that barges continued to take bone meal from the mill up to the Maltings for a few years, as the mill was not entirely dependent on supplies coming from King's Lynn. It does seem, however, that the Maltings was taking over in the fertiliser business, for Kelly's Norfolk Directory for 1900 lists 'chemical manures' as one of a number of products coming from the yards, then owned by Vynne and Everett. For several years the disused buildings of the Bone Mill remained, a forbidden playground to local children. The main building was largely intact in 1915, for a Narborough lady remembers climbing to the top that year for the view across Marham Fen. The buildings were demolished bit by bit over the next few years. The machinery went to scrap and most of the rubble was put down on farm tracks. Whenever work was slack at the Maltings a couple of men were sent down the river bank to pull down some more. Mr. Jack Bland (93), whose father-in-law worked at the mill, recalls how he cleaned and carted a load of the bricks to rebuild part of a wall round what is now the Narborough Pottery. He remembers, too, when several rotting barges were hauled out of the river in the 1940s. One of the barges had become so firmly embedded in the bank that trees grew out of it and it could not be removed. The barest remains of this barge, a few slivers of wood and the odd nail, can just be discerned at the fork where the stream from the old Narborough Corn Mill enters the main river course flowing from the Maltings. Nature has reclaimed the area where the Bone Mill once stood, with head-high nettles in summer and a thick tangle of brambles. Amongst the rubble may be seen bits of pantiles and slate, some bent tie-bars and three half buried millstones (others ended up in pieces on garden rockeries). The water swirls against the remains of the wall of the main mill building and the buff brick stanch walls are slowly crumbling away. The foundations are traceable and an underground tunnel, possibly an overflow channel which ran under the mill, may be investigated. The site and the river bank up to the Maltings are privately owned, but there is a public footpath along the opposite bank. It is worth the walk from the village to see the sixteen foot diameter waterwheel, which has a reassuring indestructibility about it. The date and maker's name must be on the section now under hard-packed debris, the last revolution of the wheel having left this piece of information inaccessible. |

Charles Boughen, farm labourer b.1851 |

James Waters, bone boiler b.1809, Weston Coleville, Cambs. |

Robert Jenkinson , coprolite grinfer b.c.1816, Hindolveston |

William Scott, millwright, b.1827, Kings Lynn

|

Bone Grinding Process |

The processes for grinding flint and bones are essentially the same. Bones would have been boiled first to remove tissue, this would in turn produce glue which could be sold as a by-product. The bones would then be moved to the calcining kiln where wood was used as fuel, not coal as would be used with flints, as bone is more combustible and prone to contamination from iron pyrites in coal. Calcinated bone becomes softer and whiter than in its natural state. The calcining kiln would have consisted of two chambers with a hovel built above them to create a draught to aid combustion. Filling the kiln was a very skilled job requiring layering of fuel and either bone or flint. Bones would be built up in layers with wood. It would be allowed to combust for 8 to 16 hours (depending on the fuel and climatic conditions) and then left to cool before being withdrawn through draw holes at the bottom. The kiln would be first heated up to 1000 centigrade, this softened the bones and made them easier to grind. Filling the kilns was a specialised task requiring careful laying of wood at the bottom and alternate layers of fuel and bone. Bone would require, because of its organic nature, little fuel once combustion had commenced and could be calcined more quickly than flint. After calcining and cooking for up to at least 8 hours the bones were then cooled enough to handle and the kiln would be hand drawn from the bottom. Any impurities would be removed, and any large bones would be cracked by hammers and or passed through a jaw cracker. The material would be taken to the pan room and tipped into the pan. These would be circular of around 12 ft in diameter with vertical sides about 3ft high. The floor of the pan would be carefully built up of chert blocks on a clay seal. A vertical shaft went through the centre of the pan for the gear drive below. The shaft would normally have 4 arms which carried vertical handing timbers. After this process any fat remaining with the one slop caused a froth and this had to be skimmed off. Following this the mixture was passed into a washtub. This would be repeated until all the sediment was at the bottom. The mixture would then be drained off so the sediment could be dried and removed in blocks. |

|

Waterwheel 1985 |

|

|

|

The

mill site c.1985

|

The

cast iron wheel c.1985 |

|

|

24th May 2009 |

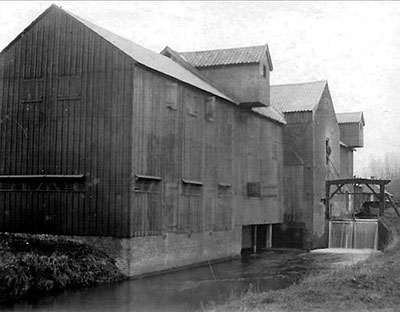

A lottery grant was optained and this allowed for restoration work to be started in 2015, thus saving the mill site from total obscurity. The renovation is well documented on the mill's own dedicated website. |

|

Site plan as drawn for the Narborough Bonemill website |

|

|

Wheelrace tunnel 2015 |

|

|

Restoration in progress - 21st November 2015 |

|

|

21st November 2015 |

|

The waterwheel

in the photograph below drove farm machinery at Hall Farm on the Narborough

Hall Estate for several years before being removed from its watercourse.

All the farm buildings were demolished in the 1980s and sadly, the wheel

was buried somewhere. |

|

|

Waterwheel

at Hall Farm c.1980

|

|

|

19th October 2017 |

|

|

|

Bone Mill renovated mill site 19th October 2017

|

|

|

|

Mill site - 20th July 2017

The stones rested on the square slabs that are in front of the railway wagon |

Pair of French burr millstones - 8th June 2017 Runner stone in foreground and bedstone behind |

|

Runner stone - upside down with the rhynd still in situ - 7th December 2017 |

Narborough Bone Mill has its own dedicated website. |

|

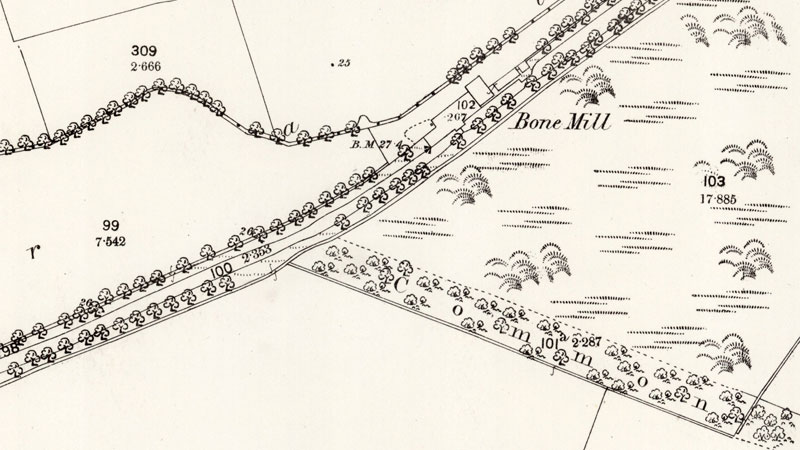

O.S. 6" Map 1884 Courtesy of NLS map images |

|

O.S. 25 " Map 1884 Courtesy of NLS map images |

|

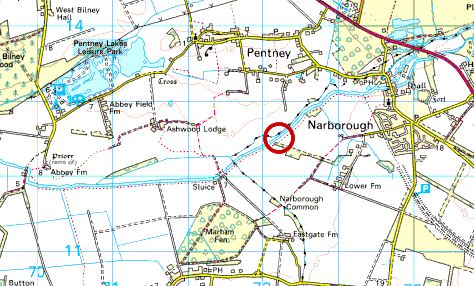

O.S. Map 2005 Image reproduced under licence from Ordnance Survey |

| c.1820: Mill

built c.1830: Mill taken over by Marriott brothers 1842: Advert in the Norfolk Chronicle named the mill as Marriott's Bone and Gypsum Mill

February 1869: William Scott, millwright died by falling into the mill machinery 21st October 1870: Charles Boughen, a farm labourer aged 19, died after a 12 foot heap of manure fell on him

Census 1881: Robert Jenkinson (55) b.Hindolveston, coprolite grinder c.1884: Mill ceased production (record may be incorrect) Census 1901: James Skerry (52) b.West Bilney, machine minder at bone mill c.1918: Building demolished over a period of time c.1975: Robin & Beryl Munford bought the maltings estate including the mill site 2015: Mill site being restored with a £92,200 lottery grant Saturday 3rd October 2015: Wheel turned by water power for first time in around 130 years |

If you have any memories, anecdotes or photos please let us know and we may be able to use them to update the site. By all means telephone 07836 675369 or

|

| Nat Grid Ref TF732125 | Copyright © Jonathan Neville 2003 |